EMDR Hacks II

/Bridging or Floating Back

One concept that is kind of difficult to convey to clients is the "bridge back," or "float back" technique, the different terms referring to similar concepts, and dependent on your therapist's style of practice. Often, if an emotional response objectively seems larger than a situation warrants, this is because it is actually related to an earlier memory, one which your conscious mind may or may not be able to connect to the current situation. If we are working on a current issue that seems to have roots in an earlier event, I will ask you to connect to the emotion of the current issue, to bring it to life with your senses, and then “effortlessly” relax into the emotion and see if your subconscious can link the emotion back to an earlier memory. This is called floating back; it's meant to be an effortless free-association.

Often in this situation, clients first try to consciously think of an earlier related memory; this can actually be counter-productive. It's best not to try too hard to understand the connection; often the connection won't be linear or make immediate sense to your conscious mind. The connection will become clear as the work unfolds. It may not be in the content of the memory, it's more likely to be in the emotion or somatic sensations that arise with the memory. In fact, when a client says "I don't think this is related, but this is what's coming up for me" or something of that ilk, I'm extra confident that we've settled on the right memory. We will then begin processing on this earlier or stronger memory, even if it seems unrelated, and as it resolves, it's often true that most, if not all, of the current issue resolves as well.

Somatic Mindfulness v. Intellectual Communication

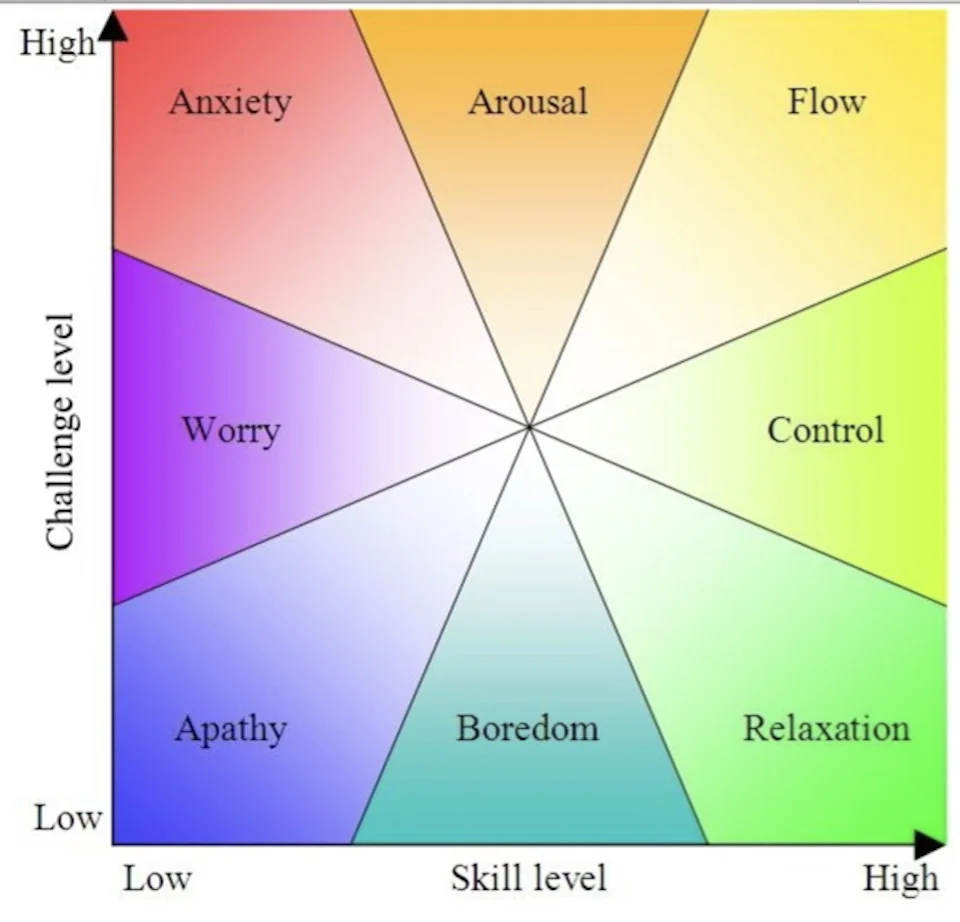

Often we experience our emotions through body sensations: we carry emotional tension and stress in our necks, our anxiety can affect our digestion or the quality of our sleep, we might notice unease in our bodies before we consciously recognize that there is a danger. When using EMDR, I will frequently ask clients to attune to their bodies and notice what is activated for them at the moment. I am especially likely to ask this when the client has been talking, interpreting, or explaining something to me.

Most therapies rely on talking, and there is the popular model of Freudian psychoanalysis, where clients lie on a couch and verbally free-associate; these are our iconic cultural norms for therapy. Many of my clients, even those who know about EMDR, come in with talk therapy as the expectation. And sometimes it’s true that things need to be spoken aloud, or witnessed.

Also true, is that talking can sometimes pull us out of our emotions; translating emotions into words is a left-brain activity, while being in our emotions is a right-brain activity. EMDR only works when we are in our emotions. Because of this, and time constraints, sometimes I will encourage clients to turn inward instead of talking, to reconnect to the body and emotions, to sit in mindfulness, and allow their present experience the opportunity to fully unfold. This doesn't mean that I don't want to know your thought processes, or that I'm not interested; I guarantee that I am very interested in the story; my curiosity is what brought me to this field. What I’m doing is prioritizing your opportunity to process things fully in the time we have available.